The Chronicles Of Shinjitsu:

Americans Of Japanese Heritage

Part Three

Race, Ethnicity, And Nationality

March 10, 2021

This is an Exclusion Order that was posted at First and Front Streets in San Francisco, California, according to The United

States National Archives and Records Administration. The Exclusion Order directed the “removal of persons of

Japanese ancestry from the first section in San Francisco to be affected by the evacuation” by April 7, 1942.

(The photograph was created by Ms. Dorothea Lange for the War Relocation Authority of the U S Department

of the Interior and provided courtesy of The United States National Archives and Records Administration, 1942.)

It’s important to consider the legal structures in place at the time of the imprisonment of Japanese Americans from 1942 to 1945. The aspects include the correlations between race, ethnicity, and nationality.

All persons born on the soil of the United States of America were – and are – citizens from birth because of certain laws, treaties, and the 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution. African Americans were initially the primary beneficiary of the passage of the 14th Amendment. Even with the passage of this constitutional amendment, though, not everyone born on American soil was considered a citizen. While some Native Americans were considered citizens of the United States through treaty agreements, that was not always the case. Eventually, almost all individuals born on American soil – including all Native Americans born on American soil – officially became citizens of the United States because of laws passed in 1924 and in 1940.

People born in other countries could become citizens of the United States through the naturalization process. That option, though, was only available to select groups of people – most of whom were born in Europe. Persons born in Japan, for example, were prohibited from becoming citizens of the United States. The United States Supreme Court ruled in 1922 that, based on the laws of this country, “…naturalization is limited to aliens being free white persons and to aliens of African nativity and to persons of African descent…” In 1924, almost all immigration from select countries – including Japan – was banned by the U S.

It was only because of a law passed in 1952 that people born in Japan – and other nations – were able to become citizens of the United States through the naturalization process.

In essence, for many decades, the United States made distinctions among Americans of Japanese Heritage between people born in Japan that were living as residents in the United States and American citizens with Japanese heritage that were born in the United States. Those distinctions did not apply when it came to the imprisonment of Japanese Americans from 1942 through 1945.

Approximately 112,000 Americans with Japanese ethnicity (according to The United States National Archives and Records Administration) were imprisoned by the Federal government from 1942 through 1945. [Other reports indicate that people imprisoned by the Federal government because of their Japanese heritage numbered approximately 120,000 persons.]

During the same time period, less than 15,000 German nationals, Italian nationals, nationals of other countries at war with the United States, American citizens with German ethnicity, American citizens with Italian ethnicity, and American citizens with ethnic heritage of other nations at war with the United States were taken into custody by the American government during the 1940s, according to a number of reports.

To put these statistics into perspective, there were 11,419,138 individuals living in the U S in 1940, according to the U S Census Bureau, that were born in another country. The U S Census Bureau reported that there were 1,237,772 individuals living in the U S that were born in Germany and that there were 1,623,580 individuals living in the U S that were born in Italy. The U S Census Bureau reported that Germany and Italy were the two nations with the largest numbers of their nationals living in the U S. Japan was not among the top 15 countries listed as having the largest number of their nationals living in the United States. (Of the top 15 countries, Scotland and England were listed separately and Canadians of French ethnicity were listed separately from all other Canadians.)

Please note: In the 1940 Census, the Federal government listed key races as “White,” “Negro,” and “Other races.” Under the term “Other races” were “Indian,” “Chinese,” “Japanese,” and “All other.”

In other words, “Japanese” people were considered a distinct race at that time. Not simply an ethnicity. Not simply a nationality.

The Federal government imprisoned Japanese Americans – both people born in Japan that were living as residents in the United States as well as American citizens with Japanese heritage that were born in the United States – that were living in several western states.

The majority of those imprisoned were living in the State of California.

Prior to the 1870 census, there were no listed Japanese individuals in California; the 1870 census indicated that there were 33 individuals living in California of the Japanese race. In 1940, there were 93,717 total – 60,148 were born in the U S and therefore citizens; 33,569 were foreign born. In other words, according to the U S Census Bureau, within the State of California, of all “Japanese,” 64.2% were native born citizens of the United States and 35.8% were born in other countries – most likely in Japan, but the Census does not state what foreign country – only that they were of the Japanese race.

(As a side note, other races listed by the U S Census Bureau in 1940 were “Filipino” and “Hindu.” “Indian” was used to designate Native Americans. “Hindu” was used chiefly to indicate people chiefly from what is today India. In 1940, the Philippines were governed by the U S as a territory of the U S.)

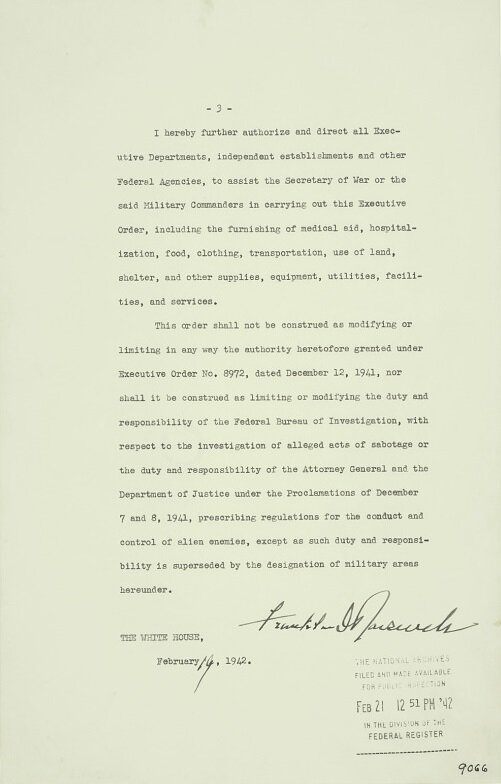

Executive Order 9066 issued by President Franklin Roosevelt was legal structure that led to the imprisonment of Japanese Americans. (The images were provided courtesy of The United States National Archives and Records Administration, February 21, 1942.)

In the next edition of The Chronicles Of Shinjitsu, we will detail how the words used by the Federal government and others during World War II and in the decades since have served to gloss over the evil implemented by the United States of America against not simply Americans of Japanese Heritage but also how those words served to suppress the American values enshrined in the United States Constitution.

Do you have questions about Japanese American communities?

A street name? A building?

Your questions may be used in a future news column.

Contact Richard McDonough at chroniclesofshinjitsu@protonmail.com.

© 2021 Richard McDonough