The Chronicles of Shinjitsu:

Americans Of Japanese Heritage

Part One

Overview

February 10, 2021

The Poston Memorial Monument is located in western Arizona on lands of the Colorado River Indian Tribes.

This memorial honors the men, women, and children who were imprisoned at this locale.

A number of Americans of Japanese Heritage from Northern California were incarcerated here from 1942 to 1945.

(The photograph was produced by and provided courtesy of Mr. Ronan Murray through Flickr, February 15, 2014.)

Darkness has befallen the United States of America at different times in our history. One of the saddest such times was when the Federal government imprisoned American citizens and residents of this nation due to racial policies. These individuals were held in horse stables (yes, horse stables) and in prisons behind barbed wire not because they committed a crime. No, instead they were taken into custody because of their Japanese heritage. Among those imprisoned were individuals and families from San Francisco to San Jose and from Sacramento to small towns throughout the region.

It was during World War II. The Empire of Japan had bombed Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, attacked the Philippines (part of the United States at the time), and invaded other locales throughout Asia and the Pacific Ocean. Japanese military personnel occupied two of the Aleutian Islands in Alaska.

These events came on top of the racial animosity towards people of Japanese descent. There was fear that Japanese-born residents of western states as well as American citizens with Japanese heritage living along the Pacific coast would attack the United States from within the country. While some made a distinction between “residents of the United States born in Japan” and “Americans citizens with Japanese heritage,” most did not. At that time, people born in Japan were prohibited from becoming American citizens.

This news column focuses on all Americans of Japanese Heritage – both American citizens with Japanese ancestry and residents of the United States born in Japan.

“One of the most stunning ironies in this episode of American civil liberties was articulated by an internee who, when told that the Japanese [Americans] were put in those camps for their own protection, countered ‘If we were put there for our protection, why were the guns at the guard towers pointed inward, instead of outward?’”

A quote from The United States National Archives and Records Administration

Japanese Americans were treated differently than other citizens and residents with heritage from other nations at war with the United States. Both Germany and Italy had more far nationals living in the U S than Japan did during World War II. There were far more American citizens with German or Italian heritage than those with Japanese heritage. Yet far fewer individuals with German and Italian heritage were imprisoned by the Federal government.

At the time – and for years afterwards – it was stated that these individuals “volunteered.” That they were “evacuated” to “assembly centers” and then transported to “relocation centers” and “relocation camps.” The more accurate words to use – the words used in this news column – are “taken into custody,” “incarcerated,” “imprisoned,” and “prisons.”

In 1988, after years of study and debate, the United States Congress and the President of the United States publicly apologized to Japanese Americans for the actions taken during World War II. Reparations in the amount of $20,000 were paid to each of the more than 82,000 individual Japanese Americans still living who had been imprisoned by the Federal government from 1942 to 1945.

“This Memorial is dedicated to all those men, women and children who suffered countless hardships and indignities at the hands of a nation misguided by wartime hysteria, racial prejudice and fear. May it serve as a constant reminder of our past so that Americans in the future will never again be denied their Constitutional rights and may the remembrance of that experience serve to advance the evolution of the human spirit.”

Part of the wording of the Poston Memorial Monument

In 1942, the U S Federal government established military exclusion zones in the western part of the country. Military Zone 1 included large sections of Arizona, California, Oregon, and Washington; the southern section of Arizona and the western portions of the three other states were included in that zone. Military Zone 2 included the remaining sections of these four states. With a few deferments (according to the Final Report: Japanese Evacuation From The West Coast – 1942, written by War Department [today’s “Defense Department”] and published in 1943), no one of Japanese heritage was allowed to remain in their homes or operate their business in Military Zone 1 as well as in the section of Military Zone 2 in California, with two exceptions. The two exceptions were that Japanese Americans were able to live in the two prisons – the Manzanar Relocation Center (Manzanar Prison) and the Tule Lake Relocation Center (Tule Lake Prison) – operated by the Federal government within Military Zone 2 in California. While a limited number of Japanese Americans left their homes in these military zones before removal was fully implemented, the vast majority of individuals with Japanese heritage were taken into custody and imprisoned by the Federal government.

According to the National Park Service, the Federal government imprisoned anyone with 1/16th or more Japanese blood from these military zones.

According to The United States National Archives and Records Administration, “From the end of March to August [of 1942], approximately 112,000 persons were sent to ‘assembly centers’ – often racetracks or fairgrounds – where they waited and were tagged to indicate the location of a long-term ‘relocation center’ that would be their home for the rest of the war. Nearly 70,000 of the evacuees were American citizens. There were no charges of disloyalty against any of these citizens, nor was there any vehicle by which they could appeal their loss of property and personal liberty.” [Other reports indicate that people imprisoned by the Federal government because of their Japanese heritage numbered approximately 120,000 persons.]

Most of the Japanese Americans were imprisoned for about three years.

Some Japanese Americans left the prisons and lived lives full of bitterness. Others remained silent – not discussing the injustice done to them and to their loved ones. Others spoke strongly against what the United States of America did to its own citizens and its own residents.

While the darkness enveloped many, some were able to see beyond the smell of the stables and the sting of the barbed wire.

“I call upon the American people to affirm with me this American Promise - that we have learned from the tragedy of that long-ago experience forever to treasure liberty and justice for each individual American, and resolve that this kind of action shall never again be repeated.”

Part of Presidential Proclamation 4417 issued by President Gerald Ford

on February 19, 1976. This presidential proclamation confirmed the

termination of the executive order authorizing the imprisonment

of Japanese Americans during World War II.

From the evil of the imprisonment of Americans of Japanese Heritage during World War II came the light of forgiveness. In the next edition of The Chronicles Of Shinjitsu, we will highlight three Americans of Japanese Heritage who rose above the fear and hatred to lives full of love.

Other future news columns will provide further details on how the Federal government considered race, ethnicity, and nationality when determining whom to imprison; what the prisons looked like; and how words have been used through the years to minimize the reality of what was done by the United States of America.

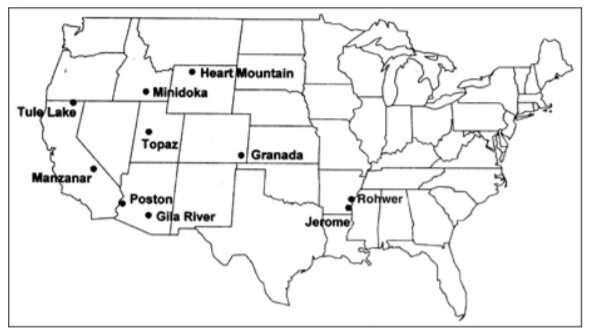

Ten “relocation camps” (prisons) were operated by the Federal government to “house” (incarcerate)

Americans of Japanese Heritage during World War II. Thousands of Americans – citizens and

residents – from San Francisco, San Jose, Sacramento, and other communities in the region were

imprisoned for years in these locales. In most cases, local Americans of Japanese Heritage were

incarcerated in the Gila River, Granada, Heart Mountain, Poston, and Topaz Prisons.

(The map was provided courtesy of the National Park Service.)

Credits:

The photograph of the Poston Memorial Monument was produced by

and provided courtesy of Mr. Ronan Murray through Flickr, February 15, 2014.

The map was provided courtesy of the National Park Service.

No copyrights to these images are held or claimed by Richard McDonough.

Do you have questions about Japanese American communities?

A street name? A building?

Your questions may be used in a future news column.

Contact Richard McDonough at chroniclesofshinjitsu@protonmail.com.

© 2021 Richard McDonough