Syndication News Column:

Americans Of Japanese Heritage

Part One

Forgiveness

The Poston Memorial Monument is located in western Arizona on lands of the Colorado River Indian Tribes.

(The photograph was produced by and provided courtesy of Mr. Ronan Murray through Flickr, February 15, 2014.)

Darkness has befallen the United States of America at different times in our history. One of the saddest such times was when the Federal government imprisoned American citizens and residents of this nation due to racial policies. These individuals were held in horse stables (yes, horse stables) and in prisons behind barbed wire not because they committed a crime. No, instead they were taken into custody because of their Japanese heritage.

It was during World War II. The Empire of Japan had bombed Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, attacked the Philippines (part of the United States at the time), and invaded other locales throughout Asia and the Pacific Ocean. Japanese military personnel occupied two of the Aleutian Islands in Alaska.

These events came on top of the racial animosity towards people of Japanese descent. There was fear that Japanese-born residents of western states as well as American citizens with Japanese heritage living along the Pacific coast would attack the United States from within the country. While some made a distinction between “residents of the United States born in Japan” and “Americans citizens with Japanese heritage,” most did not. At that time, people born in Japan were prohibited from becoming American citizens.

Japanese Americans were treated differently than other citizens and residents with heritage from other nations at war with the United States. Both Germany and Italy had more far nationals living in the U S than Japan did during World War II. There were far more American citizens with German or Italian heritage than those with Japanese heritage. Yet far fewer individuals with German and Italian heritage were imprisoned by the Federal government. Please click here for further details of how the Federal government considered race, ethnicity, and nationality when determining whom to imprison.

At the time – and for years afterwards – it was stated that these individuals “volunteered.” That they were “evacuated” to “assembly centers” and then transported to “relocation centers” and “relocation camps.” The more accurate words to use – the words used in this news column – are “taken into custody,” “incarcerated,” “imprisoned,” and “prisons.” As noted in the accompanying news column, the more accurate words to use would be “imprisoned” and “prisons.” Please click here for further details on these definitions.

In 1988, after years of study and debate, the United States Congress and the President of the United States publicly apologized to Japanese Americans for the actions taken during World War II. Reparations in the amount of $20,000 were paid to each of the more than 82,000 individual Japanese Americans who had been imprisoned by the Federal government from 1942 to 1945 and were still with us at that time.

Less than 50 miles from Silver City was a military exclusion zone. Established in 1942, Military Zone 1 included large sections of Arizona, California, Oregon, and Washington; the southern section of Arizona and the western portions of the three other states were included in that zone. Military Zone 2 included the remaining sections of these four states. With a few deferments (according to the Final Report: Japanese Evacuation From The West Coast – 1942, written by War Department [today’s “Defense Department”] and published in 1943), no one of Japanese heritage was allowed to remain in their homes or operate their business in Military Zone 1 as well as in the section of Military Zone 2, with two exceptions, in California. The two exceptions were that Japanese Americans were able to live in the two prisons – the Manzanar Relocation Center (Manzanar Prison) and the Tule Lake Relocation Center (Tule Lake Prison) – operated by the Federal government within Military Zone 2 in California. While a limited number of Japanese Americans left their homes in these military zones before removal was fully implemented, the vast majority of individuals with Japanese heritage were taken into custody and imprisoned by the Federal government.

According to the National Park Service, the Federal government imprisoned anyone with 1/16th or more Japanese blood from these military zones.

According to The United States National Archives and Records Administration, “From the end of March to August [of 1942], approximately 112,000 persons were sent to ‘assembly centers’ – often racetracks or fairgrounds – where they waited and were tagged to indicate the location of a long-term ‘relocation center’ that would be their home for the rest of the war. Nearly 70,000 of the evacuees were American citizens. There were no charges of disloyalty against any of these citizens, nor was there any vehicle by which they could appeal their loss of property and personal liberty.” [Other reports indicate that people imprisoned by the Federal government because of their Japanese heritage numbered approximately 120,000 persons.]

Most of the Japanese Americans were imprisoned for about three years.

“One of the most stunning ironies in this episode of American civil liberties was articulated by an internee who, when told that the Japanese [Americans] were put in those camps for their own protection, countered ‘If we were put there for our protection, why were the guns at the guard towers pointed inward, instead of outward?’”

A quote from The United States National Archives and Records Administration

Some Japanese Americans left the prisons and lived lives full of bitterness. Others remained silent – not discussing the injustice done to them and to their loved ones. Others spoke strongly against what the United States of America did to its own citizens and its own residents.

While the darkness enveloped many, some were able to see beyond the smell of the stables and the sting of the barbed wire.

This news column details the stories of several American citizens. Individuals with Japanese heritage who were denied their constitutional rights. Persons who were imprisoned not because they did anything illegal, but were held in custody because of their ethnicity.

And yet, these individuals were able to forgive the United States of America for what was done to them and what was done to their loved ones.

Forgiveness is something taught by most of the major religious faiths in our country and throughout the world.

Yet it is exceptionally difficult for some of us to forgive those who hurt us – sometimes in situations that are simply irritating, sometimes in situations that are extremely painful: A person with 24 items is in front of you at the grocery store – in the lane that has a 10 item limit. You discuss an idea to enhance your workplace with a coworker, and the coworker then takes your idea to your boss; your boss loves the idea, and your coworker gets a promotion for her “excellent” idea. Your husband had an affair with your best friend. It can be difficult to forgive in these situations (even something as modest as having too many items in a grocery lane).

Forgiveness does not come easy for many of us.

And yet, people who were denied their freedom – their liberties – were able to forgive those who hurt them and caused pain for their loved ones.

Mary Kinoshita Higashi

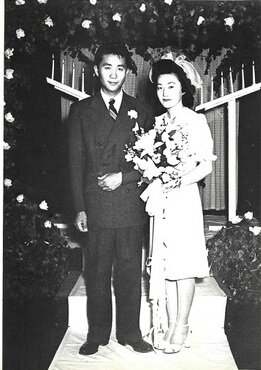

Mary Kinoshita married Paul Masata Higashi on May 23, 1945. The wedding

took place in the prison operated by the Federal government in Poston, Arizona.

(The photograph was provided courtesy of Paula Higashi, 1945.)

Mary Kinoshita Higashi was one of those individuals.

She was a 19 year-old teenager attending Bakersfield Junior College (now known as “Bakersfield College”) in Bakersfield, California. She was a few weeks away from graduating with her college degree when the then Mary Kinoshita and her family were imprisoned at the Poston Relocation Center (Poston Prison). This prison was established by the Federal government on lands of the Colorado River Indian Tribes in Arizona. Please click here for several photographs of the Poston Prison.

According to the State of Arizona, a total of 17,867 people with Japanese heritage were incarcerated at the Poston Prison located near Parker, Arizona. Most of the people imprisoned here were citizens of the United States of America; their “crime” was being of Japanese heritage.

“When I was in the Camp, being that I was a Christian, we went to Sunday School every Sunday, and I was able to...Well, you don't forget, but you forgive what happened,” Mrs. Higashi stated in a panel discussion at California State University, Bakersfield, on January 30, 2018. “What the government did was wrong. But we were able...We had to accept it because we were always taught you abide by the law. You don't go against the law. And since the order [Presidential Proclamation 9066 issued by President Franklin Roosevelt on February 19, 1942] came out, we just obeyed and we did what we were told to do. And so, after the evacuation, we talked about it freely. And I forgave the government. And I was able to live with myself, and I had a very happy life. If I had that anger in me and hostility, I wouldn't have been able to live happily. In fact, if you didn't know, I'm 95 years old. And I've just been blessed, I think, because of my attitude.”

Paula Higashi, a daughter of Mary Kinoshita Higashi, explained that her mother “and others referred to the war years with the Japanese phrase, ‘Shikata ga nai.’ I always understood this to mean that ‘it can’t be helped’ or ‘nothing can be done about it.’ I would like to think that this Japanese phrase or cultural concept…contributed to the incredible resiliency of my mother and her generation. Instead of dwelling on the negative, they lived each day as it came and tried to make the best of it…The fusion of her understanding of ‘Shikata ga nai’ and her Christian beliefs made her a person who did not hold grudges and could forgive others, including the U S government, for their sins.”

In October of 1990, Paula Higashi explained, President George H. W. Bush sent a letter to Mary Kinoshita Higashi and other Japanese Americans on White House stationery: “A monetary sum and words alone cannot restore lost years or erase painful memories; neither can they fully convey our Nation’s resolve to rectify injustice and to uphold the rights of individuals. We can never fully right the wrongs of the past. But we can take a clear stand for justice and fully recognize that serious injustices were done to Japanese Americans during World War II. In enacting a law calling for restitution and offering a sincere apology, your fellow Americans have, in a very real sense, renewed their traditional commitment to the ideals of freedom, equality, and justice. You and your family have our best wishes for the future.”

Mrs. Higashi was born in the United States of America in 1922; she died in 2018.

“This Memorial is dedicated to all those men, women and children who suffered countless hardships and indignities at the hands of a nation misguided by wartime hysteria, racial prejudice and fear. May it serve as a constant reminder of our past so that Americans in the future will never again be denied their Constitutional rights and may the remembrance of that experience serve to advance the evolution of the human spirit.”

Part of the wording of the Poston Memorial Monument

Alice Setsuko Sekino Hirai

Alice Setsuko Sekino Hirai.

(Photograph provided courtesy of Mr. Stan Hirai.)

Alice Setsuko Sekino Hirai was a small child when she was deemed by the Federal government to be a threat to the people of the United States. She was imprisoned with her family initially in a horse stable at the Tanforan Assembly Center (Tanforan Prison) located just south of San Francisco in San Mateo County, California. She and her loved ones were then moved to the Topaz Relocation Center (Topaz Prison) built by the Federal government near the City of Delta in Millard County, Utah. Please click here for several photographs of the Tanforan and Topaz Prisons.

“Love is stronger than hate,” stated Mrs. Hirai. “If we love more, this tragedy won’t happen again…I am proud to be an American where our government apologized to us.”

She was a nurse for 54 years and a strong advocate for the disabled, especially education for children with disabilities. She spoke eloquently about educational needs for these children – including for one of her daughters, Marlene. Marlene, at the age of 52 years of age, died in February of 2020.

Mrs. Hirai herself died at the age of 77 years in 2016; she had been born in the United States of America in 1939.

On March 21, 2017, the City of Ogden posthumously honored Alice Setsuko Hirai with the presentation of a plaque to her family. The plaque stated that she was being honored for “...her lifetime of service...Her lessons have taught the importance of love and preventing history from repeating itself...We are saddened by her passing...We are beholden to lessons Alice has taught to the community and are we confident that her legacy will continue for many years to come...”

“I call upon the American people to affirm with me this American Promise - that we have learned from the tragedy of that long-ago experience forever to treasure liberty and justice for each individual American, and resolve that this kind of action shall never again be repeated.”

Part of Presidential Proclamation 4417 issued by President Gerald Ford on February 19, 1976. This presidential proclamation confirmed the termination of the executive order authorizing the imprisonment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

Aiko “Grace” Obata Amemiya

Aiko “Grace” Obata Amemiya.

(Photograph provided courtesy of the Iowa Department of Human Rights.)

Aiko “Grace” Obata Amemiya and her family were initially housed at the Turlock Assembly Center (Turlock Prison) that had been sited at the Stanislaus County Fairgrounds in Turlock, California. She and her loved ones were then transported to the Gila River Relocation Center (Gila River Prison) on the land of the Gila River Indian Community in central Arizona. This prison and the Poston Prison, both operated by the Federal government, eventually became two of the four largest “cities” in the State of Arizona; only Phoenix and Tucson had larger populations than the Poston and Gila River Prisons from 1942 through 1945. Please click here for several photographs of the Turlock and Gila River Prisons.

At the time of her imprisonment, Mrs. Amemiya was a 21-year-old student at the School of Nursing at the University of California, San Francisco. “While Grace was in Gila, she used the nursing skills she had learned in nursing school,” according to the Iowa Department of Human Rights. “She was desperately needed for this service since even persons who had been in nursing homes and hospitals were taken away to internment camps.”

Think about that statement.

“Even persons who had been in nursing homes and hospitals were taken away…”

Leaders of the United States of America made the decision that elderly people and individuals with disabilities being cared for in nursing homes as well as patients at hospitals were to be imprisoned by the Federal government. Because they had Japanese heritage.

According to the Iowa Department of Human Rights, “Grace was determined to complete her education when internment ended, and she wrote to nursing schools around the country. Many of them told her they didn’t need any more of ‘her kind’ in their school and she was rejected. Finally, she was accepted at St. Mary’s School of Nursing in Rochester, Minnesota. She spent her final six months of nurses training as a senior cadet nurse in the U S Cadet Nurse Corps, working at Schick General Army Hospital at Clinton, Iowa.” A woman – an American citizen – imprisoned by the Federal government for no other reason than her ethnicity chose to help heal and care for the individuals wearing the uniform of our country.

Mrs. Amemiya spoke of forgiveness in many locales.

In California, she spoke up for those – like herself – who had been denied graduation because of the actions of the Federal government. Mr. Bill Kidder of the University of California, Santa Cruz, said of Mrs. Amemiya: “I do remember her general outlook was one of forgiveness and not bitterness.” Mr. Kidder was one of several individuals who worked to have the University of California award honorary degrees to Japanese American alumni forced to leave the University due to imprisonment by the Federal government.

Another individual involved in those efforts was Mr. Daniel Simmons, now Professor Emeritus of the School of Law at the University of California, Davis. He, too, recalled the words of Mrs. Amemiya: “Her remarks to the University of California Board of Regents when we sought regental approval for the honorary degree program were moving...”

In 2009, ceremonies were held to award honorary degrees to Mrs. Amemiya and to other former students of the University of California.

“My most vivid memory of the program comes from the University of California, Davis, ceremony,” explained Professor Simmons. “Sitting as part of the stage party, I watched several Japanese American veterans of World War II standing at attention with their hands over their hearts during the National Anthem. Their service to their country in the face of the terrible evil that we inflicted on Japanese American citizens of the United States and their extraordinary dignity virtually moved me to tears. As I tried to say in remarks on the day of the University of California, Davis, ceremony, I hope that the diversity within our contemporary institutions of higher education will help to assure that we never repeat the terrible mistakes of 1942.”

In 2016, the State of Iowa honored Mrs. Amemiya for her service to the American people. At the age of 95 years, she was inducted into the Iowa Women’s Hall of Fame. The Iowa Department of Human Rights noted that Mrs. Amemiya told her story – “this story of grace, forgiveness, and service through hundreds of speeches across the state of Iowa and beyond.”

Mrs. Amemiya was born in the United States of America in 1920; she died in 2017.

Her first name – “Aiko” – means “Love” in Japanese.

As we conclude Year 2020, may we remember the need for forgiveness.

Remember Mary, Alice, Grace, and all of the others.

They and their loved ones survived living in horse stables, behind barbed wire, and in temporary barracks.

They rose above the hatred, the fear, and the discrimination.

Their willingness to forgive touched many.

Their brightness of spirit illuminated the light that eventually extinguished the darkness.

May we never forget.

© 2020 Richard McDonough